The content of this page has not been vetted since shifting away from MediaWiki. If you’d like to help, check out the how to help guide!

In ImgLib2, images are represented by Accessibles. Image here refers to any (partial) function from coordinates to values.

In the previous section we have seen how pixel values can be manipulated using Accessors. Accessors are obtained from Accessibles. For example we have used:

final Cursor< UnsignedByteType > cursor = img.localizingCursor();

to obtain an iterating accessor from the Accessible img.

Accessibles represent the data itself. Pixel images, procedurally generated images, views into images (for instance sub-images), interpolated images, sparse collections of samples, the list of local intensity maxima of an image, list of nearest neighbors, etc., are all examples of Accessibles.

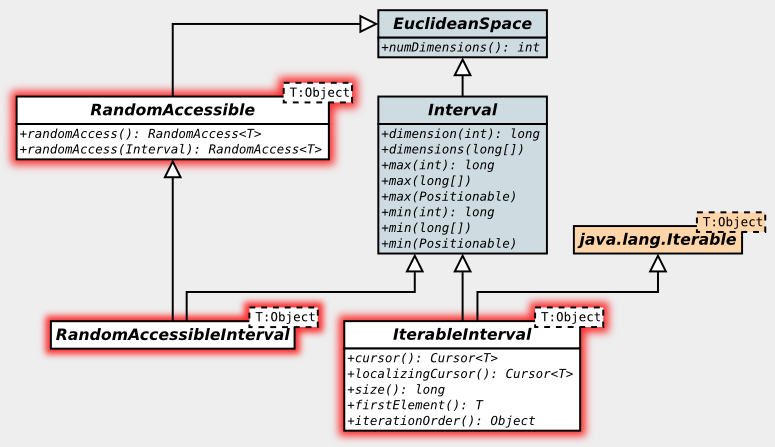

The UML diagram below shows the integer part of the Accessible interface hierarchy. We will look at the full diagram including Accessibles for real coordinates later. Accessible interfaces have been highlighted.

UML for ImgLib2 integer accessible interfaces

RandomAccessible and RandomAccessibleInterval represent images that are random-accessible at integer coordinates. (Remember: an image is a - possibly partial - function from coordinates to values.) You can obtain a RandomAccess on the data using the randomAccess() or randomAccess(Interval) methods.

All ImgLib2 classes representing pixel images are RandomAccessibles. We already used this in a previous example to obtain a RandomAccess on an ArrayImg.

final RandomAccess< UnsignedByteType > r = img.randomAccess();

IterableInterval represents an iterable collection of samples at integer coordinates. You can obtain a Cursor using the cursor() or localizingCursor() methods. You can obtain the number of elements using size(). The first element can be obtained by firstElement() which is a short-cut for cursor().next().

RandomAccessibleInterval and IterableInterval represent bounded images where all samples lie within an interval. Both extend Interval which defines methods to obtain the minimum, maximum, and dimensions of the interval. Dimensions refers to the extend of the interval in every dimension, and is defined as maximum - minimum + 1. You can obtain the maximum and minimum in a single or all dimensions. If you obtain it in all dimensions, it can be stored into a long[] array or a Positionable. (Have a look at the Interval API doc.)

RandomAccessibles

By convention, a RandomAccessibleInterval represents a function that is defined at all coordinates of the interval. A RandomAccessible on the other hand might be defined only partially. You should be aware of this when creating RandomAccessibleIntervals. For instance it is straightforward to turn a RandomAccessible into a RandomAccessibleInterval by adding interval boundaries. If you do so, it is your responsibility to ensure that the RandomAccessible is fully defined within these boundaries.

There are two randomAccess methods, one taking an Interval argument and one without parameters (see RandomAccessible API doc). By using the first method, randomAccess( Interval interval ), you specify that you will use the returned RandomAccess only within the given interval. Some RandomAccessibles provide optimized access on restricted intervals. The second method, randomAccessible() returns a RandomAccess that covers all coordinates where the RandomAccessible is defined. The reason for having both variants is that some RandomAccessibles may provide optimized accessors for specific sub-intervals. Procedurally generated images might be precomputed for certain intervals, boundary condition checks might not be required in certain intervals, etc. All ImgLib2 classes representing pixel images return the same accessor for both methods. However, when writing generic algorithms that work on arbitrary RandomAccessibles, consider using the interval method.

IterableIntervals

There are two methods for obtaining Cursors, cursor() and localizingCursor(). These typically return different Cursor implementations.

The localizingCursor() keeps track of its location whenever you move it forward. When you localize it it will just return that pre-computed location. It is more efficient when localization occurs frequently. For example when you want to compute the centroid coordinates of an iterable list of samples, you would use a localizing cursor.

The cursor() only calculates its position when it is localized. For instance when you want to find the maximum value in an IterableInterval you are not interested in the locations of all the samples. You just want to localize the cursor once, at the maximum.

Every IterableInterval has an iterationOrder(), that is, a defined sequence in which its values are visited.